This article originally appeared in the Gordie Center's 2019 print publication.

September 17, 2019, marks the passing of 15 years since Lynn Gordon “Gordie” Bailey, Jr. died a preventable, senseless hazing death at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Fifteen years feels like a long time ago, and somehow still like yesterday for his mother and stepfather, Leslie and Michael Lanahan. They can recall in painstaking detail where they were when they learned of Gordie’s death, and it’s incredibly difficult to think about that time. Leslie had talked to Gordie on the phone shortly before he left for the fraternity pledging ceremony that killed him.

“Gordie called Leslie as she and I were driving down to Austin for a meeting. Gordie was really happy to tell us that he had made the lacrosse club as a freshman. It was a 2-minute phone call because he had to rush off — he told us that he was accepted to pledge at Chi Psi, and had to go get dressed up for the pledging ceremony,” Michael remembers.

“I think about that phone call a lot. If Leslie had handed me the phone, would I have said, ‘Be careful?’ Having been in a fraternity, I’m not sure I could have given him the warnings — in my experience, we didn’t have a ceremony that would have people drink to excess and put their lives in danger. It wasn’t something I was thinking about at the time, so would I have even said that to him?”

The fact that they didn’t know what their son was about to face, or that alcohol overdose was possible and deadly, is why Leslie and Michael didn’t retreat after Gordie’s death — instead, they felt compelled to take action to prevent other families from feeling their same pain and loss. As hard as it was to share Gordie’s story through their grief, they wanted Gordie to not be forgotten. Their boy had lived 18 years, and hazing couldn’t steal that time from them like it stole his future.

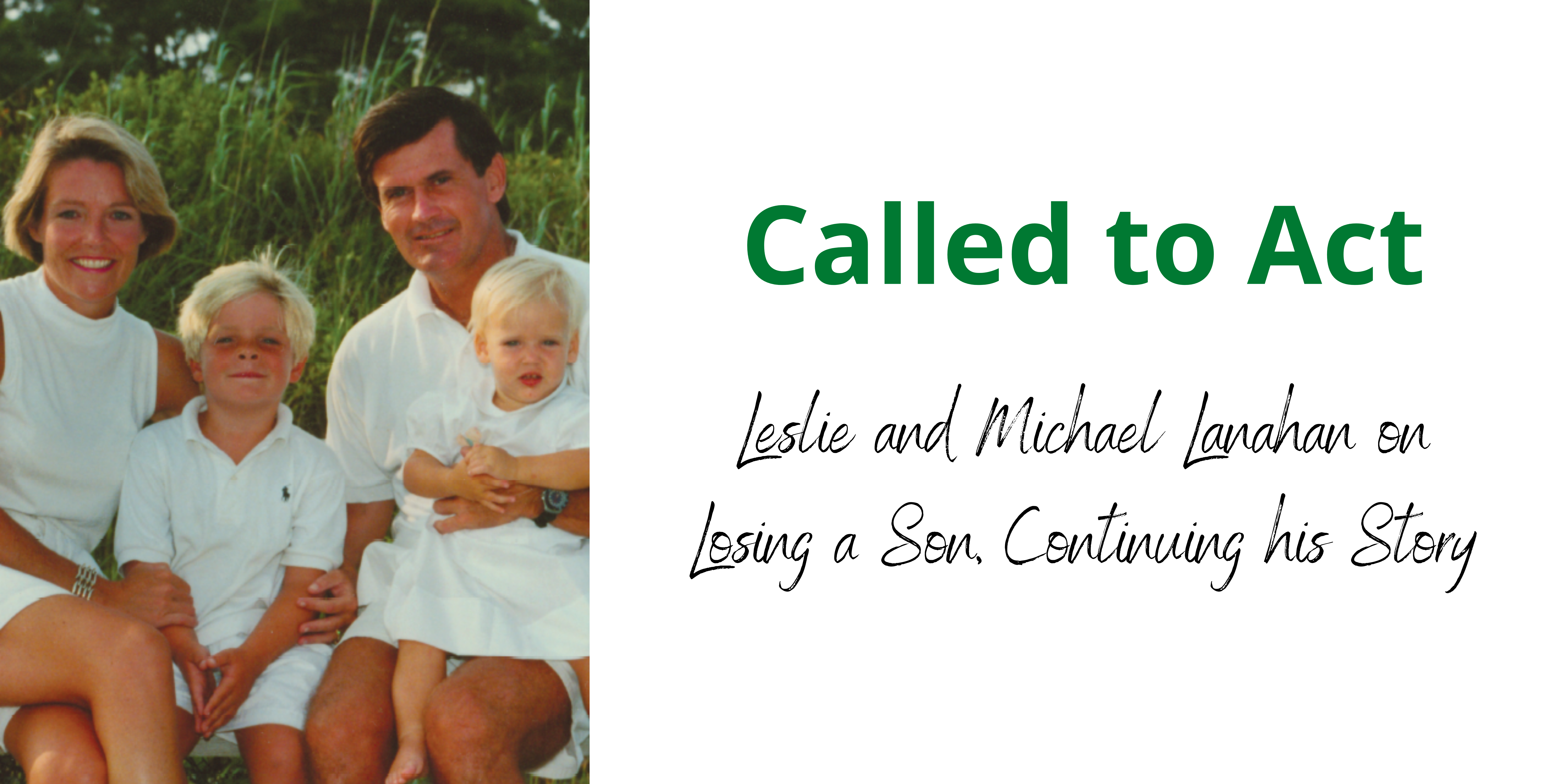

Gordie Bailey, 1986 — 2004

Gordie was born in Connecticut on February 22, 1986, and was the first child for Leslie and her then-husband, Lynn Gordon Bailey, Sr. When Gordie was a baby, Leslie was working toward a degree in interior design at the New York School of Interior Design, after having been an advertising executive in New York and San Francisco. She felt design school was a great way to build the foundation for a career that would allow her flexibility, and to be home with her kids as they grew up. “I didn’t want to be on a train commuting from Connecticut and be gone all day — I wanted something more creative and something I could do from home.” After Leslie and Lynn divorced, Leslie and Michael were married and she moved to Dallas, TX, with 3-year-old Gordie. Michael was in Dallas pouring his time and energy into Greystone Communities, the company he founded in New York City in 1982. A daughter for Leslie and Michael followed a year later — Lily was born shortly after Gordie’s 4th birthday.

“As a child, Gordie was so busy,” Leslie says with a laugh. “He was like a giant golden retriever. He was so loving and eager to please. Thankfully, we found the perfect school for him in Dallas — Lamplighter School, whose campus is like a farm with animals. He attended Lamplighter until 4th grade, and it was perfect for him — he was sword fighting, jumping all over, just busy. It was very hands-on, and Gordie thrived in a creative environment. He became really good with computers and technology — even developing video games. He really was creative — his first grade teacher told me he was a renaissance man. I’m not musical, but boy, was Gordie musical — he just loved singing and playing instruments since he was a baby. He was always front and center dancing — he didn’t have a shy bone in him. He was just going to do what he wanted to do — he marched to his own drum.”

In 5th grade, Gordie transitioned to the all-boys St. Mark’s School of Dallas. “Gordie was always looking forward. When he got out of 4th grade, he was so excited to be going into 5th grade — always looking forward to the next year,” Michael says. Gordie stayed at St. Mark’s through 9th grade, making the varsity football and lacrosse teams as a freshman. “He scored the winning goal in overtime against lacrosse rival Highland Park as a freshman — it was great!” Leslie smiles at the memory. Those years were wonderful for the family. Lily had started at Lamplighter School as well, but the lack of structure wasn’t for her — Leslie and Michael moved her to Episcopal School of Dallas in 2nd grade. Michael’s company thrived, and Leslie served as a docent at the Dallas Museum of Arts for 12 years. The family spent their summers in Sun Valley, Idaho, where Gordie’s dad and stepmom lived — it was a blessing in their lives that Gordie’s four parents were good friends. Leslie and Michael took the kids on vacations to Europe and Jamaica — they all had the travel bug, and enjoyed being together.

During Gordie’s 9th grade year, Leslie and Michael began researching boarding schools for him — Leslie attended The Taft School in Connecticut, and Michael attended St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire, so boarding school was part of their family tradition. Gordie toured his parents’ alma maters, as well as Phillips Academy Andover and Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts.

“When we toured Deerfield, I saw the students wearing coats and ties, and I thought, ‘Gordie definitely won’t want to go here — too many rules.’ When we got back in the car, he said, ‘That’s where I’m going.’ He loved it. I think a lot of it was the campus — he loved the layout, because it was more like a college campus. He loved standing out because he was from Texas — his junior year, he won an award for his declamation, where he had to stand up and recite his paper in front of the whole school. His paper was about being a Texan in the Northeast — he wasn’t really that big of a Texan, but he played it up. He liked that he was different that way,” Leslie recalls. Michael adds, “He couldn’t have been happier to get the experience at Deerfield away from home.” Gordie embraced everything that Deerfield had to offer — he played varsity lacrosse and football, had the lead in the school play, and most importantly for him, he developed close friendships.

Senior year, he served as a Proctor in his dormitory, mentoring younger Deerfield students. He could often be found with his guitar, hanging out with friends, or in front of the TV with his buddies watching a football game. Leslie, Michael, and Lily came up to Deerfield frequently to cheer at his games and watch him on stage in the theater. “A standout athlete who also stars in the school play … Gordie never took the path that people would expect somebody to go. He wasn’t a renegade or revolutionary, but he saw a different path for himself. He was good at math … we never saw him studying, but he always did well on tests,” says Michael. Leslie echoes, “He had a lot of things going for him — he was very creative, artistic, and athletic. Things came easily for him. The joke was that he never graced the door of the Deerfield library.”

The University of Colorado (CU) in Boulder presented itself as an opportunity after Gordie was disappointed by his lack of acceptance at his top college choices. “Gordie didn’t apply himself at Deerfield until it was too late,” Leslie remembers. “He really wanted to go to the University of Virginia or Washington & Lee, and he didn’t get into either.” Leslie suggested that he apply to CU because her sisters had gone there. He loved snowboarding and the outdoors, so he decided to make the most of CU. He graduated from Deerfield Academy in May 2004, and in the last week of August, Gordie and his family moved him into his dorm room to begin the next exciting chapter in his life.

September 2004

One week after moving Gordie to CU, Leslie and Michael moved Lily from their home in Dallas up to Connecticut, where she began 9th grade at Leslie’s alma mater, The Taft School. Having both kids out of the house was an adjustment for Leslie and Michael — they wanted to respect Gordie and Lily’s independence, but still wanted to be in the loop. On September 16, Leslie and Michael were driving from Dallas to Austin for a Baylor Hospital board meeting, and Gordie called them to check in. That quick phone call was reassuring as parents — Gordie was finding his niche in a large school, and really sounded happy. The next day, September 17, Leslie and Michael received the horrible phone call that Gordie had died. They were stunned and confused and absolutely devastated. It was pure chaos. They quickly decided that Michael would go to Boulder (meeting Gordie’s dad and stepmom there) to deal with whatever needed to be done, and Leslie would go to Lily, who was 14 years old and had been away from home for only two weeks. Leslie couldn’t get to Lily fast enough.

“I was frantic to get to her, and I was so worried about her,” remembers Leslie. She had to tell Lily about her brother while in the airport — Leslie had called the headmaster at Taft, informed him, and had him get Lily so that Lily wouldn’t be alone when she heard the news. Then Leslie made her way through the airport alone. “I had to connect in Chicago, and I walked up to the gate with my ticket … Gate 4A. Except that wasn’t my gate at all — I had misread my ticket, and gone to the gate with the same number as my seat assignment on the plane. The gate attendant had to say, ‘Ma’am, that’s your seat assignment — not your gate.’ I was in the totally wrong part of the airport for my flight — I was just in a trance.” Michael was having an equally tough time in Boulder. He had to identify Gordie in the morgue and collect his things from the dorm room. “Gordie’s roommate Steve and friend Jack told me stories about Gordie, trying to help us understand … but they didn’t even understand. They were 18 years old, and Gordie’s death was senseless.” Michael met with the Chancellor at CU at the time, who told Michael that he, as Chancellor, didn’t have the authority to crack down on the fraternities for hazing because the fraternity houses weren’t on university property.

“I told him that he should resign if that was his response to me when I was there to pick up our dead son. The lack of concern and leadership at the university level was astounding. I can’t tell you how angry I was. Being the stepdad, I was a little more removed and had more anger than Leslie.”

Michael brought Gordie’s body home to Dallas. Leslie and Lily returned to Dallas, and Leslie was able to see Gordie and say goodbye to her firstborn. Fourteen-year-old Lily stood up and spoke at her brother’s memorial, stayed home in Dallas for that week, and then returned to Taft to resume 9th grade.

“It was perfect that Lily was at Taft. I was so glad she went back. I was really glad she didn’t have to see me every day — it was the right thing. I never wanted her to feel like she had to take care of me, or worry about me. She got to go and grow and learn and have lots of new fun experiences, and she just thrived. We went up there every other weekend,” Leslie says of Lily’s decision to go back to Taft after Gordie’s death. Michael remembers worrying about Lily’s ability to focus when she returned to school, because he was struggling at work. “I couldn’t understand what priority I had when I sat at my desk at work — work was very confusing. I couldn’t put one foot in front of the other. It was really good for Lily that she wasn’t home. Leslie didn’t want to get out of bed — Gordie’s death was tough for me as a stepdad, but watching my wife lose her son was so hard. Our family of four had disintegrated.”

"Gordie was my best friend from the first days I can remember up until the day he died. I don’t think I have gone more than a few days without thinking about him. I often have dreams where Gordie just shows up out of nowhere and I ask him, “Where the hell have you been?” before we start catching up. I wake up with the same pain that I experienced when I heard he had died.

I know Gordie would have been immensely successful professionally and socially. Whenever I have some sort of milestone in my life, it makes me wonder what and where Gordie would be doing if he were still alive.”

— Gregory Clement, Gordie's childhood best friend

Creating The Gordie Foundation

Very quickly after Gordie’s death, the Lanahans realized that they needed to do something to combat their feelings of helplessness … Gordie was gone, but they would work to prevent another family from experiencing a loss like theirs. They formed The Gordie Foundation (TGF) to share Gordie’s story and lifesaving message. Support poured in from family and friends to help get TGF started.

“When we formed TGF, we brought a group of friends together from different backgrounds and thought through different goals and strategies. We wanted to keep the message simple, and focus on educating students and families that alcohol can kill. As parents who have lost a son, we have a responsibility to share what we have learned. We have a responsibility to be out there leading the charge on education,” Michael says of the effort behind forming the Foundation. “I think that if somebody had picked up the phone and made a call, Gordie would be alive today. That’s such a simple thing. He laid on that couch for I don’t know how many hours, and nobody did anything. I think that’s true of all these hazing deaths. Our call to action was ‘Save a Life, Make the Call’ — it’s a pretty simple call to action. Gordie would still be with us if someone had called to get him help.”

A major undertaking of TGF was producing a documentary film about Gordie and the factors that led to his death. Leslie and Michael worked with director Pete Schuermann to capture Gordie’s personality, interview his friends, and explore the problem of hazing and alcohol overdose on college campuses. The result of their efforts is the documentary HAZE, which was released in 2008 (a new edit of the film, including a stronger focus on hazing, was released on Gordie’s birthday in 2018).

“I love HAZE — I think the film has this magical ability to bring Gordie’s personality to life. He is such a presence in the film that you just relate to him. That’s the way he was … even if you weren’t his kind of person, you couldn’t help but like him—he was loveable, huggable, and so funny. Everyone can relate to him,” Leslie says of the film. HAZE is shown annually at high schools and colleges nationwide.

“Focusing on the Foundation was inspirational and gave us a goal and focus,” says Michael. “It was part of our survival. It was a full-time job. At the same time, we wanted to make sure that Lily was doing as well as she could do, and that we weren’t spending so much time on the Foundation that she felt slighted. My goal was to try to show Lily what we thought the appropriate response to a tragedy was. We were hoping she would be proud of what we were doing on behalf of her brother to educate and change. There are other tracks we could have taken, and we were more right than wrong in the path we took with the Foundation.”

As much as TGF helped Leslie and Michael, their grief was still overwhelming. Leslie remembers, “For the first five years, you just can’t even believe it. You wake up every day and you think, ‘Are you kidding me? How can this be?’ For me, around year 7 or 8, I started to believe it — he was gone, and he wasn’t coming back. Then it was just trying to figure out how to live with that. Now, I know he’s gone and this is our reality. I had to keep going, for Lily … if I hadn’t had her, I don’t know what would have happened.”

Leslie and Michael were managing their own emotions while also trying to be there for each other. “We were all lucky to get through it,” Michael states matter-of-factly. “Not many parents lose a child and stay together — many get divorced. Because I was Gordie’s stepfather, I was slightly removed … so I was able to take care of Leslie more than needing to take care of myself.” Leslie is effusive about Michael. “I’m so grateful for Michael — he did such a great job. I don’t know that I would have gotten through it if it was any different. You can’t really help the other person who loses their child — they are so all-consumed.”

The Lanahans were involved in the day-to-day operation of TGF for over five years. During that time, the family moved to a new house in Dallas, away from the home where they had raised Gordie and Lily — it was too difficult to live where memories of Gordie permeated every space. The new house provided some distance from the constant emotional strain of living among those memories — the move was emotional, but also provided a merciful relief. For that same reason, the Lanahans began actively searching for a new home for their nonprofit in 2010 — living every day with reminders of Gordie’s death through their work with the Foundation was taking a toll. Michael attended the University of Virginia’s (UVA) Darden School of Business, and had maintained his connection with UVA since his graduation. UVA seemed like a natural home for TGF, and in late 2010, the Lanahans gifted their foundation to UVA, where it became the Gordie Center.

After the shift, it was necessary for the Lanahans to take a step back — as Leslie put it, “You want to climb under a rock and not hear anything about it for 20 years.” They continued to be updated on the work the Gordie Center was doing, and enjoyed the separation from the daily emotions. A few years passed with less involvement on their part, years spent on healing and finding balance in their lives again. They never strayed far, though, and since 2016, the Lanahans have taken on a more active advisory role with the Gordie Center staff. They consult closely on the Gordie Center’s efforts to ensure that Gordie’s lifesaving message continues to impact students nationwide. Michael says of the Gordie Center that “Gordie’s message is in good hands. We have heard anecdotally about the lives Gordie’s story has saved, and I think there are even more that we haven’t heard about. I think it’s one of the proudest things of my life.” Leslie feels similarly. “I’m immensely proud of the fact that there is still work going on in Gordie’s name. Any parent who has lost a child … you just want your child not to be forgotten, so the work being done in his name is meaningful to our whole family. I’ve gotten a lot of feedback that Gordie’s story has helped people and saved lives — even still — and that makes me feel really good.”

15 Years and the Future

Fifteen years is a long time to live without your child. Leslie has tried to balance her grief with the reality that life goes on for her, and for Gordie’s friends. “I didn’t do a Christmas card for 4 years, and then I finally decided to do it for Lily. There will always be that big hole in your heart. You just try to focus on the positive — celebrate the good and learn to live with the bad. I’m used to living without him. It’s terrible, but I’m used to the fact that he’s not here. It’s not as raw — you grow a pretty thick skin. I’d like to think that there was value in Gordie’s short life of 18 years — it meant something to a lot of people. You just can’t believe his life was so short. Time goes on. His friends are getting married and having kids. So few people understand — they don’t even connect that it would be hard for Michael and me.” Michael gives an example to illustrate Leslie’s point: “Gordie’s high school was playing for the state lacrosse championship recently, and friends wanted us to come out, and Leslie couldn’t do it. Even now, watching Gordie’s buddies get married, it’s really tough. Gordie should be in that picture — he should be getting married, he should be having children. We love to be around Gordie’s friends, but it is so hard.”

Michael has felt his grief change over the years as well: “In the early years, you feel like there’s a stump on your chest that almost won’t allow you to breathe and won’t go away. As the years go on, the stump is still there, but you’re able to put it in a safe place and you deal with the reality that things aren’t going to change. Gordie’s not coming back. Time is circular. We have his birthday, Mother’s Day, the anniversary of his death, and Christmas every year. We have to face these things without him. I always think of this analogy: When you break a leg, you realize how many other people are walking around with casts on. There are so many people who have suffered tragedies, and they just keep on going — that’s just what you do in life. Leslie and I have a very healthy dialogue and ability to talk about Gordie, and we try to do it often. Some of our family and friends still don’t know how to talk with us about our dead son — they don’t want to upset us or make us cry, but it doesn’t hurt us to cry in front of people. We had a son that we like to talk about. He was a great son.”

On the especially hard days, like Gordie’s birthday, Leslie and Michael choose to celebrate who Gordie was. Michael says they ask themselves, “What would Gordie do? We watch a movie that Gordie loved, like Dumb and Dumber, we laugh a lot, eat a philly cheesesteak, and think about all the joy Gordie brought us."

Fall is challenging every year, not only because of the anniversary of Gordie’s death, but because the Lanahans watch as hazing continues and more families lose loved ones.

“It’s hard because, frankly, not that much has changed in 15 years!” Leslie laments. “It can be draining. I think there is great value in numbers — there is a huge opportunity for families who have lost children to join together to raise awareness. We are a club that no one wants to join, and we don’t want more members. There’s a great opportunity for our families to come together and help make the world aware of how often these tragedies are happening. They happen one at a time, so it’s very hard to build momentum.” Michael takes an even more direct stance: “By definition, we have failed in our mission because so many families have lost a child after Gordie died. Every one of those deaths was a failure on our part — why didn’t they get the message, why didn’t the parents know, why haven’t colleges and fraternities tried to implement safer policies?”

Fifteen years has also given Leslie and Michael time to reflect on their efforts with the Gordie Center, and the message they want to give to students and parents. “I think my message has evolved,” Leslie says. “In the beginning, it was about taking care of your friends. We were focused on what to do in a tragedy: make sure you call for help. Now, I am more interested in how to prevent the tragedy from happening. How do we make sure hazing doesn’t happen? We need to focus on changing the traditions. Hazing is ugly and mean, and there’s no need for it. How can we help foster bonding in a more positive way? You don’t need alcohol to bond. You don’t need to humiliate someone to bond. We need to be talking with these young men and changing the traditions. I think taking care of your friends is always important, but how can we stop hazing before it starts?"

Michael embraces the call to action that started The Gordie Foundation, and expands on it. “If there’s a broader context of warning your son — when he joins a fraternity, as he takes a leadership position, warn him. Kids are dying during hazing. They are more susceptible 30 days into college in the fall — why can’t we change the system and make pledging spring of sophomore year? If it could happen to Gordie, it could happen to anybody’s kid. When you look at the profile of these hazing deaths, they were pretty stand-out kids. They were not shrinking violets. Gordie never got hurt in athletics, so he was more willing to take risks. During the hazing the night he died, Gordie did more than his share because he was looking out for the other pledges — he thought he could handle it. He had an 18-year-old brain and thought he was invulnerable. We talked with Gordie a lot about drinking and driving. We never talked to him about alcohol poisoning, and we failed Gordie in that respect. When you lose a son the way we lost Gordie, it’s like — why didn’t we get the memo, why weren’t we able to give him the right education before he went to college?”

“Part of the answer is education — education about the dangers, what to be on the watch for, but also education about the people who have been killed through this process and what the laws are doing to try to address the problem,” Michael continues. “A lot of that is transparency — if people are able to see which fraternities are killing their pledges, what number, which schools … there are a lot of repeat offenders. Parents who haven’t yet sent their kid to college don’t even know what to worry about — that’s why transparency is important. I don’t think the Greek system even registers for parents at orientation with their son. The reason it’s hard to change the system is because all the hazing is secret — you only hear about it if they kill a pledge. And even then, it’s hard when you are losing one boy at a time to get the public to say, ‘We aren’t going to stand for this anymore.’ There’s so much opportunity for change. My hope is that at some point this reaches a tipping point. I don’t know how many deaths that would require. Those in a position of authority at universities and in the Greek system nationwide just hope to wake up on a Sunday morning and learn that no one has died, because they aren’t really doing anything to prevent it or change it.”

Leslie and Michael have spent the last 15 years grieving the loss of their son, pushing for change so that other families don’t have to endure what they have been through, and honoring Gordie in the way they live their lives now. Leslie thinks a lot about the impression that her son left on so many. “He was sweet and loveable, one of the funniest kids in the whole world — people just wanted to be his friend because he was fun. Gordie made the most of his life, and he would like anybody to learn to do the same. No one is more surprised to have died like this than Gordie. He would never have wanted to put his family through this type of pain. He always thought he could handle things, and so did I. The hardest part about the 15 years is learning to live with the tragedy — it’s something I can’t do anything about. It takes so much energy, living with it. You feel so badly about it, but there’s nothing you can do about it. Having other people learn through his story and not put their families through the same pain would be important to Gordie.”

Michael thinks about what was lost when Gordie died, not just for their family, but for Gordie. “It’s hard to put into words the loss, and it’s hard to do it in a way that families who haven’t experienced it can appreciate. We don’t want other people to experience it. We want to make a difference and prevent other families from losing their child. We always talked about when Gordie finally found his passion, he was going to be extraordinary. He wasn’t the best student, but he was brilliant. I always thought he would end up behind a camera, directing … but we could also see him as a football coach. He loved to diagram plays, loved sports, loved kids. I don’t think he would have been sitting behind a desk like his stepfather. He was always going to take a different path. It’s heartening to think about all those possibilities, and sad that it was cut short.” After a pause, Michael adds, “I feel like I was given too much time. I would gladly give up that time to give Gordie 30, 40 more years. He would have been extraordinary.”